Cat-Loving Haruki Murakami and the Abundance of Movie Adaptations

Cat-Loving Haruki Murakami and the Abundance of Movie Adaptations

Disclaimer: This article purports to shed some light on Aum Shinrikyo and how the cult's image is reinvented by means of cinema. Needless to say, nothing in this article shall be construed as supporting, endorsing, or promoting domestic terrorism or religious fanatism in any way.

What alternative is there to the media’s “Us” versus “Them”? The danger is that if it is used to prop up this “righteous” position of “ours” all we will see from now on are ever more exacting and minute analyses of the “dirty” distortions in “their” thinking. Without some flexibility in our definitions we’ll remain forever stuck with the same old knee-jerk reactions, or worse, slide into complete apathy. ~ Haruki Murakami (Underground)

It has been 26 years already since the infamous Tokyo subway attacks. As a person from Central Europe who was barely three years old at that time, I have no recollection of the event, and probably the same applies to many non-Japanese readers of this article. Nevertheless, it cannot go unnoticed that this incident is, to date, the deadliest act of terrorism carried out on Japanese soil.

It continues to be reiterated and remembered in Japanese culture through visual, literary, and digital means. However, it does not change the fact that there has never been a live-action adaptation of how Aum Shinrikyo shocked an entire nation on a quiet morning of March 20, 1995. Having been inspired by Haruki Murakami’s gripping book Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche, I embarked on a research journey to find out what remained of Japan’s most controversial cult. The aim of this text is to explore cinematic reflections of Aum Shinrikyo.

In Sonshi* We Trust: Crimes of the Cult |

Commuters waiting outside of one of the subway stations (March 20, 1995).First of all, some introductory information is required for readers who may be unfamiliar with the subway incident and the circumstances surrounding it. That is to say, on the 20th of March, 1995, five members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult boarded trains cruising back and forth three Tokyo subway lines: Marunouchi, Chiyoda, Hibiya. Between 7:50 and 8:00 a.m., they punctured special plastic bags which contained sarin, a nerve gas that leads to muscle paralysis, respiratory distress, loss of vision, and ultimately death.

Commuters waiting outside of one of the subway stations (March 20, 1995).First of all, some introductory information is required for readers who may be unfamiliar with the subway incident and the circumstances surrounding it. That is to say, on the 20th of March, 1995, five members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult boarded trains cruising back and forth three Tokyo subway lines: Marunouchi, Chiyoda, Hibiya. Between 7:50 and 8:00 a.m., they punctured special plastic bags which contained sarin, a nerve gas that leads to muscle paralysis, respiratory distress, loss of vision, and ultimately death.

Because of the fact that the gas was manufactured in home-made conditions and it was not spread as efficiently as it was originally planned, the attack caused the death of only 13 people, but at the same time, it led to either temporary or permanent physical impairment of approximately 6,000 commuters who travelled by train on that day.

The police quickly concluded that Shoko Asahara was responsible for devising the attack, and they arrested the leader together with his associates. The trial that ensued lasted for years and eventually ended with a death penalty for Asahara and twelve other members of Aum.

Haruki Murakami attempted to provide an objective account of the tragedy, devoid of sensationalist media frenzy. Consequently, we get to read many testimonies of those who survived the subway attacks as well as the ones who used to be in Aum. Out of bits and pieces of information provided by these people, we can compose the following image of Shoko Asahara: His real name was actually Chizuo Matsumoto. He was born as a half-blind child in a low-income family, and after receiving education in the discipline of acupuncture, he became fascinated with Buddhism. In the 1980s, he set up a yoga-teaching group which eventually evolved into Aum Shinrikyo.

Initially, Asahara had noble intentions. He wanted to help out people troubled by physical ailments or stress and, allegedly, took no charge for his services. All of a sudden, the group became a very enclosed structure based on hierarchy. Newcomers had to pay a high fee (from 10 to 30,000 yen) to sign up, and later much more in order to receive teachings from Asahara, which were a mixture of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Christianity. What is more, the students had to do a fixed amount of prayers, meditation and also watch hours of special videos with Asahara’s preachings. All of that contributed to the good deeds of the follower, which enabled him or her to climb the ranks of the group.

Screenshot from Chouetsu Sekai anime. |  Rare image of Aum followers while praying. |

How the group used to promote itself in the public stratum was also quite extraordinary. There were books, magazines, music(!), recruitment campaigns, special TV appearances of Asahara (yes, the media did not shy away from validating his persona before 1995), and even anime… That’s right, Aum Shinrikyo used to produce its own OVA with the benevolent leader as its main protagonist. It’s just as cringy as you think, and you can check out the whole thing on YouTube. The first episode even received fansubs.

In spite of all this merchandise stir, the exploitation of followers continued to take place. In order to prove their usefulness, they had to participate in special seminars, spread promotional leaflets, or help in building Shinrikyo’s facilities spread across Japan. If the follower had a higher education or was just a good looking female, they received a quicker promotion in the process of the supposed enlightenment. Eventually, they were encouraged to become monks and thus had to donate all of their life savings to the cult. In this manner, Aum Shinrikyo amassed enormous wealth in the early 1990s.

At this point, one could ask the following questions. What exactly did Aum Shinrikyo offer to newcomers? Why was it so appealing? Haruki Murakami infers in his short essay “Blind Nightmare: Where Are We Japanese Going” that many people felt disillusioned with their lives, education, and social pressures. They did not see any point in or were downright afraid of, independent lifestyle. They were looking for a utopia, a complete contradiction of the Japanese way, which required them to be the best at school, get a job, get married, and die having accomplished nothing. By this way of reasoning, Shoko Asahara offered these people a refuge, but it came with a price, which was to give up social contacts with anyone outside of Aum and also renounce any form of material wealth. Aum Shinrikyo’s appeal lied not in its New Age exoticness but in its superficial innocence; it seemed to be just another yoga school for people seeking their promised land.

A police officer stands guard outside the Aum Shinrikyo cult headquarters 6th compound (Kamikuishiki) as the raids continued on May 11, 1995. The compound was razed to the ground by the authorities in 1996.

A police officer stands guard outside the Aum Shinrikyo cult headquarters 6th compound (Kamikuishiki) as the raids continued on May 11, 1995. The compound was razed to the ground by the authorities in 1996.

It is difficult to estimate when Asahara started losing his grip on reality. He began preaching about the impending apocalypse, the Third World War between America and Japan, bound to happen in 1997. This kind of rhetoric put off a certain amount of followers, but they were forcefully made to stay in the group, even if it cost them their lives. Consequently, in 1989, Aum Shinrikyo brutally killed an anti-cult lawyer, Tsutsumi Sakamoto, and his family, just because he was fighting in defense of members held against their will. Later on, in 1993, Aum tried to spread airborne anthrax from one of their Tokyo facilities, but the endeavour had minimal effect. In 1994, with the usage of sarin, they successfully killed judges who were supposed to investigate the real-estate controversies surrounding the organization. None of these crimes was attributed to Aum before March 1995.

What was the reasoning of Asahara to conduct the attacks? To date, they remain unclear because the cult leader in question never revealed them. Some researchers claim that he believed in his prophecies and wanted to quicken the end of the world, but a more pragmatic explanation seems to be the most appropriate. That is to say, Asahara was so power-hungry that he wanted to poison and kill all of the politicians and police officers in Tokyo, which would enable him to take control over Japan and declare himself the Emperor.

Perspectives of Discrimination: Victims vs. Aum |

A nurse helping one of the victims (March 20, 1995).What ensued in terms of media coverage in 1995, as underlined by Haruki Murakami, was the convenient us vs. them dichotomy: presenting Aum Shinrikyo and all of its members as warmongering fanatics while painting the image of Japanese services working at full capacity to save innocent victims. Unfortunately, the reality is that the emergency units were completely unprepared for such a cataclysmic event. People from the subway had to stop taxi driver so as to rush victims in need to hospitals. Those affected never received proper media coverage as well. Television never spoke about people with permanent disability or family members who lost their loved ones. The coverage was watered down, and it focused primarily on representing the cult as a bunch of terrorists in possession of guns and biochemical weapons.

A nurse helping one of the victims (March 20, 1995).What ensued in terms of media coverage in 1995, as underlined by Haruki Murakami, was the convenient us vs. them dichotomy: presenting Aum Shinrikyo and all of its members as warmongering fanatics while painting the image of Japanese services working at full capacity to save innocent victims. Unfortunately, the reality is that the emergency units were completely unprepared for such a cataclysmic event. People from the subway had to stop taxi driver so as to rush victims in need to hospitals. Those affected never received proper media coverage as well. Television never spoke about people with permanent disability or family members who lost their loved ones. The coverage was watered down, and it focused primarily on representing the cult as a bunch of terrorists in possession of guns and biochemical weapons.

In Murakami’s Underground, we can hear the testimonies of people who were affected by the subway attacks. Widows and parents in mourning, injured station-masters or angry siblings. For instance, Kenji Ohashi suffers from constant headache which affects his work duties, Yoshiko Wada singlehandedly raises her daughter after the untimely death of her husband, and Kazo Asakawa looks after his physically disabled sister, Sachiko. Specifically, Mrs Wada recalls how she was harassed by the media and how they distorted a TV interview she agreed to participate in. In another case, a subway survivor was accused of being a terrorist just because he resembled an identikit. These are the stories inconvenient for the nationalist narrative, which strives to convince ordinary citizens that Japan always emerges triumphantly even from the worst tragedies. The truth is that had it not been for the ineptitude of law-enforcement services, perhaps the attacks might have been prevented.

In the period between 1995 and 2012, all of the culprits participating in the subway attacks and preceding crimes have been arrested; however, the police still continue to observe the cult and raid its facilities, fuelling in this way the media frenzy. Undoubtedly, Shoko Asahara planned the attack together with his closest associates, but hundreds of members within the cult had no idea about the impending danger. On the 20th of March, many of them heard about what was going on in Tokyo, but they did not believe that Aum was behind this. Because it was proven later that Aum was responsible, many people had to leave the cult in order to avoid discrimination. Frequently, they divided themselves into small groups and tried to live just as within the cult but formally outside of it; nevertheless, if someone somewhere found out through the media which these people were, they consequently lost their jobs and were evicted from their apartments.

A (1998) by Tatsuya Mori |

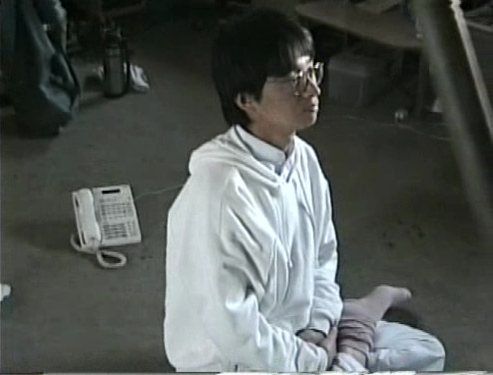

Hiroshi Araki while meditating.In 1998, an independent filmmaker Tatsuya Mori released a documentary simply titled A, in which he presented the everyday life of Aum Shinrikyo members (those who stayed in the cult) after the 1995 incident. We see them continuously worshipping Shoko Asahara while struggling to acknowledge the brutal outcomes of their leader’s horrific actions. They pray in front of his image, listen to special audio recordings, and also battle media reporters waiting for them in front of the training facilities. This is the time capsule of the group on the brink of destruction as told through the perspective of Aum’s young deputy spokesman, Hiroshi Araki.

Hiroshi Araki while meditating.In 1998, an independent filmmaker Tatsuya Mori released a documentary simply titled A, in which he presented the everyday life of Aum Shinrikyo members (those who stayed in the cult) after the 1995 incident. We see them continuously worshipping Shoko Asahara while struggling to acknowledge the brutal outcomes of their leader’s horrific actions. They pray in front of his image, listen to special audio recordings, and also battle media reporters waiting for them in front of the training facilities. This is the time capsule of the group on the brink of destruction as told through the perspective of Aum’s young deputy spokesman, Hiroshi Araki.

Interestingly, we see them working in spartan conditions day by day and enjoying their simple plight. Whatever negative happens to them, they simply treat it as the release of bad karma. Perhaps the most disheartening image in the whole documentary is a recording of the police raid in the course of which the officers try to take out a crying child from a dark, enclosed chamber while they are struggling with his mother. Surprisingly, the child is wearing a special helmet with wires that are supposed to aid him to receive the brainwaves of Shoko Asahara.

As Araki travels between different facilities, which are either to be demolished or to be liquidated, Mori records an image of a distraught man who, while thinking about his family, struggles to keep the publicly hated organisation together. The ambiguity of this documentary raises some moral concerns: Are these people truly brainwashed? Should they be allowed to pursue their concept of utopia even if their leader turned out to be a terrorist? Does the police have any right to harass them? Mori neither acknowledges nor answers these questions. He objectively points the camera at the followers of Asahara and gathers their complex confessions.

Woman in Witness Protection (1997) by Juzo Itami |

Nobuko Miyamoto as Biwako Isono, a witness of the gruesome murder.The late director Juzo Itami always crafted his movies around the topical concerns which troubled society, and Woman in Witness Protection is no exception. As a matter of fact, Itami focused on the issue of cults as early as 1988 in A Taxing Woman’s Return, where Ryoko (Nobuko Miyamoto), an IRS agent, investigates an insidious religious group that is suspected of tax evasion.

Nobuko Miyamoto as Biwako Isono, a witness of the gruesome murder.The late director Juzo Itami always crafted his movies around the topical concerns which troubled society, and Woman in Witness Protection is no exception. As a matter of fact, Itami focused on the issue of cults as early as 1988 in A Taxing Woman’s Return, where Ryoko (Nobuko Miyamoto), an IRS agent, investigates an insidious religious group that is suspected of tax evasion.

In Woman in Witness Protection, we follow Biwako Isono (Nobuko Miyamoto), a shallow and spoiled movie star. All of a sudden, she witnesses a gruesome murder of an anti-cult lawyer and his wife. In order to protect the actress from religious fanatics, the police provide her with specially trained witness protection officers until the trial. In the meantime, Biwako has to deal with various means of harassment and attempts to tarnish her public image.

To put it in simple terms, Woman in Witness Protection is Juzo Itami’s middle finger towards Aum Shinrikyo. By means of his usual black comedy style and brutal satire, the director exposes the fallacies of the cult and how it engages in domestic terrorism. The premise of the story is actually based on the real-life murder of Tsutsumi Sakamoto and his family. In addition, Itami can’t help himself but name Aum and Asahara in one of the interrogation scenes when police officers try to disprove the might of the glorious “Guru” by stating that he actually can’t levitate.

All in all, Woman in Witness Protection is a very clever comedy drama, but this is not to say that the film is free from ghastly sequences. In a Tarantino-like manner, Itami underlines the fact that nothing will stop religious fanatics from accomplishing their goals (even if it means threatening, bribery, or killing).

Cure (1997) by Kiyoshi Kurosawa |

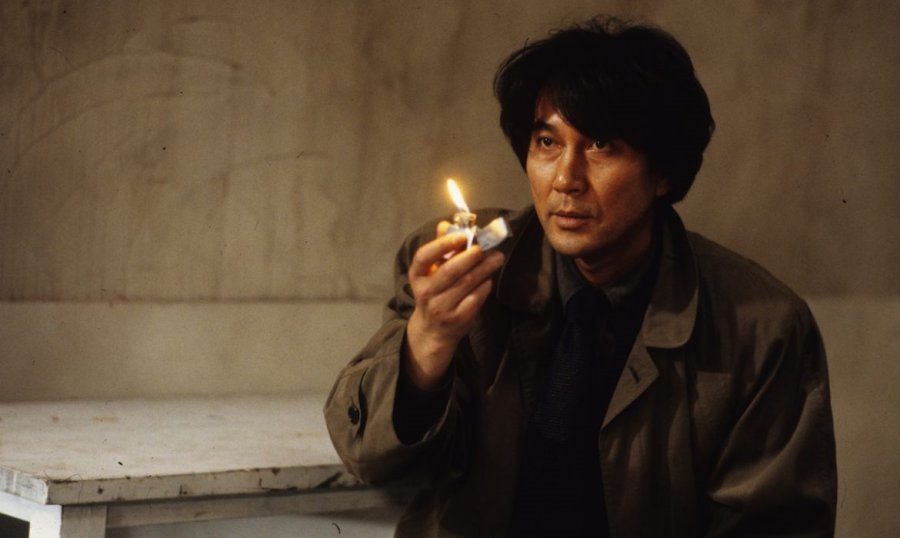

Koji Yakusho as Detective Takabe while confronting mysterious Mamiya.Although director Kiyoshi Kurosawa never acknowledged the influence of Tokyo attacks on the making of his low-budget psychological thriller, I can’t help but think about the subway tragedy in the context of riveting Cure. Similarly to Woman in Witness Protection, the movie came out just two years after the incident, and it tackles in a bleak and serious tone the issue of sanity within modern society.

Koji Yakusho as Detective Takabe while confronting mysterious Mamiya.Although director Kiyoshi Kurosawa never acknowledged the influence of Tokyo attacks on the making of his low-budget psychological thriller, I can’t help but think about the subway tragedy in the context of riveting Cure. Similarly to Woman in Witness Protection, the movie came out just two years after the incident, and it tackles in a bleak and serious tone the issue of sanity within modern society.

Detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho) is investigating a series of strange murders. The culprits are caught after the act, and they claim not to know what pushed them to kill a person that was close to them. Every case has one thing in common, the victims died from blood loss resulting from a wound made in the shape of an X mark. Suddenly, the police detain a man called Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), who suffers from memory loss. Takabe is convinced that Mamiya is responsible for the killings because he possesses extraordinary hypnotic power.

Surprisingly, Kurosawa does not rely on overt gore or jump scares. The unsettling feeling of Cure lies within its mood and themes. From the first few scenes, you think that the film is going to play out like an ordinary police procedural, but all of a sudden, things make a U-turn, and we get a frightening tale as if cooked up by Stephen King himself.

In a society that thrives on hierarchy and teamwork, it is disheartening to see the main protagonist looking after his mentally ill wife. It is effortless to assume that she is a subway survivor, while Mamiya functions as an Asahara-like manipulator who penetrates the psyches of his victims and, in accordance with his own twisted reasoning, liberates them through morbid acts. With its critique of the Japanese social insensitivity, Kiyoshi Kurosawa moves dangerously close to the dogma of Aum Shinrikyo, which glorifies the breakaway from earthly desires and human contacts.

Eureka (2000) by Shinji Aoyama |

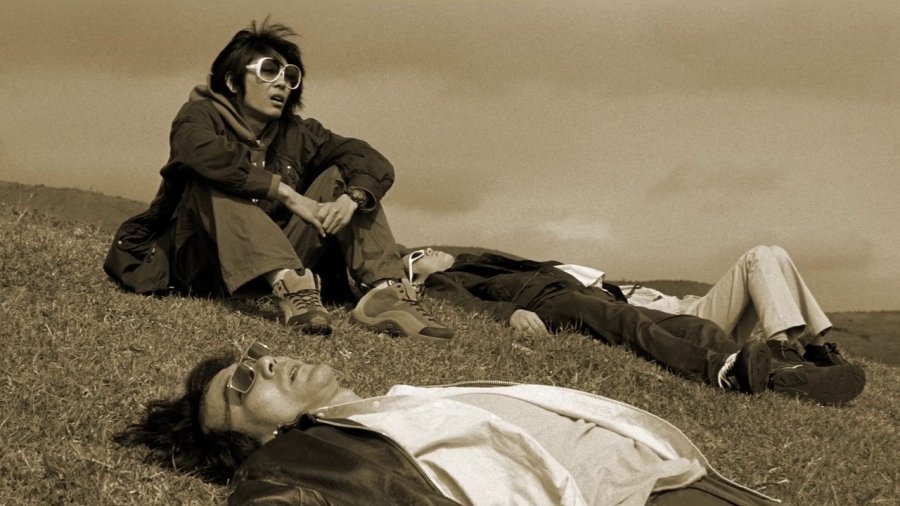

Shinji Aoyama’s Eureka is an arthouse masterpiece, shot in sepia tone, which carefully examines the impact of a traumatic event on its victims. The director admitted that he was inspired by the 1995 subway attacks to tackle this difficult subject.

The main protagonists of the film are two siblings, Naoki (Masaru Miyazaki) and Kozue (Aoi Miyazaki), as well as a bus driver, Makoto (Koji Yakusho). They are the only survivors of a hijacking incident. We see these characters losing their family and connection with reality. They attempt to live normally, but there is always some kind of intrusion. It is only in the film’s culminating moment when Kozue and Makoto realise that they can live happily.

The movie truly feels like a consolation letter to all the victims of Aum Shinrikyo. Emphasizing that there is always a chance for hope, regardless of how grim the situation is. Nevertheless, if a victim is not careful enough, despair may push him or her into madness.

Me and the Cult Leader (2020) by Atsushi Sakahara |

AGANAI Me and The Cult Leader: A Modern Report on the Banality of Evil is a 2020 documentary directed by Atsushi Sakahara. I believe it is best to describe it as a spiritual companion piece to Tatsuya Mori’s A (1998) because we see the director (a survivor of 1995 events) travelling through Japan with none other than Hiroshi Araki himself (now a chief spokesman of the Aleph cult).

Paradoxically, we get a follow up on the protagonist of Mori’s documentary over 20 years later. Together with Sakahara, we see the interiors of Aleph (who still worship Asahara), but we also gain further insight into the troubled soul of Araki. It is finally revealed how the spokesman became influenced by Aum Shinrikyo and how a personal tragedy pushed him to join the cult.

At the same time, Sakahara also shares a painful story. Being not just the victim of Aum’s subway attack, he also married a former Aum member (whose duties and involvement within the cult still remain a mystery). What is more, Sakahara and Araki actually derive from the same mountain region in the Kyoto prefecture (though their families live in different towns).

AGANAI documentary (literal meaning: Atonement) really goes on to show that life works in mysterious ways. It made me feel sorry for both protagonists, who are, in a way, victims of Shoko Asahara’s fanaticism: Sakahara struggles with PTSD and damage to his nervous system, while Araki left his family to devote himself entirely to the cult.

Conclusions |

Shizue Takahashi, whose husband was killed on March 20, 1995, lays flowers at one of the stations.All things considered, Haruki Murakami claims that we should learn from this tragedy rather than forget it. The writer postulates reforming the Japanese education and social relations, which push youngsters into depression. He emphasizes that the Japanese people purposely averted their eyes from the Aum problem just because they thought it was not their concern. Aum, in turn, heavily radicalized itself when it started seeking autonomy from national constraints. The author also likens the glorification of Asahara to the unwavering cult of the Emperor during the Second World War.

Shizue Takahashi, whose husband was killed on March 20, 1995, lays flowers at one of the stations.All things considered, Haruki Murakami claims that we should learn from this tragedy rather than forget it. The writer postulates reforming the Japanese education and social relations, which push youngsters into depression. He emphasizes that the Japanese people purposely averted their eyes from the Aum problem just because they thought it was not their concern. Aum, in turn, heavily radicalized itself when it started seeking autonomy from national constraints. The author also likens the glorification of Asahara to the unwavering cult of the Emperor during the Second World War.

On the other hand, psychologist Robert Jay Lifton, the author of Destroying the World to Save It. Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism warns that the phenomenon of Aum Shinkriyo should not be treated as a distinctly Japanese anomaly. He compares the subway attacks to Jim Jones’ the Peoples Temple, concluding that these terrorist acts were motivated by a religion-charged obsession with the apocalypse. Murakami adds that while the main culprits were judged in the court of law, we should not fall into generalization and be prejudiced against ex-members of the cult. Under appropriate circumstances, all of us could have joined the group.

Factual Addendum:

In spite of numerous appeals and a personal campaign of Shoko Asahara’s daughter to exonerate her father, the leader was hanged together with twelve associates in July 2018. Asahara’s lawyer stated that group execution was performed so quickly in view of the approaching Tokyo Olympics.

Although Aum Shinrikyo was officially disbanded in 1996, the cult continues to exist under the guise of at least two organizations: Aleph and The Circle of Light. To date, they remain under the surveillance of law enforcement services (and it has been proven that Aleph still worships Asahara). In 2016, the Russian government labelled Aleph as a terrorist group and shut down its facilities. In 2019, an Aleph sympathizer rammed his car into a crowd of bystanders in order to voice his protest against the execution of Asahara. As for the victims of the attack, they continued to hold anniversary memorials until March 2020, when the pandemic spread across the globe.

Pain is invisible, and known only to the sufferer (Underground).

*Sonshi: meaning master.

Sources: Aum Shinrikyo: Images from the 1995 Tokyo Sarin attack * Cult members hanged for Tokyo subway attack, and other crimes * Film aims to pass the memory of 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack to young * How a yoga school became a doomsday cult * Japan marks the 25th anniversary of deadly Tokyo subway attack by cult * Japan remembers subway gas attack, 20 years on * Destroying the World to Save It. Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism by Robert Jay Lifton * Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche by Haruki Murakami * Shoko Asahara: my memories of how Tokyo subway sarin attack spread terror one day in March 1995 * Woman bedridden since AUM cult's 1995 sarin gas attack on Tokyo subway dies at 56 * Zero Hour Terror in Tokyo (documentary) produced by Discovery Channel * Bacillus anthracis incident, Kameido, Tokyo, 1993 * Rika Matsumoto Interview * Atsushi Sakahara Interview *

Ebisuno92’s Previous Articles: For Comrade's Eyes Only: Interview with Johannes Schönherr (with Seonsaeng) * Takeshi Kitano Is Gearing Up to Direct His Final Film "Kubi" * From Zero to Hero: A Retrospective Guide to Yaguchi Shinobu (with Joe Shiren) * An Ultra Fan's Guide to Takeshi Kitano * An Ultra Fan's Guide to Kyoko Kagawa * Feel the Power of Office Ladies: Shomuni Retrospective * "Watashi, Shippai Shinai No De!”: Daimon Michiko as the Ultimate Doctor-Hero (with Reika Bleu) * "Come on over, Spiritual Phenomena!” TRICK, A Franchise Retrospective * From Best Korea with Love: An Introduction to North Korean Dramas & Movies (with Seonsaeng) * Cursed Cassettes, Countdowns, and Corpses: A SFW Guide to the Ring Series * Blast from the Past: Did Bayside Shakedown Destroy Japanese Cinema? * Weekend Recommendations: Father Knows Best * Godzilla's on the Loose: 65 Years of Kaiju Rampage * An Ultra Fan’s Guide to Yeoh Michelle * Blast from the Past: A Guide to “Girls with Guns” Genre * Weekend Recommendations: Old School Movies * Ebisuno92's Weekend Movie Picks *

This was my look at Aum Shinrikyo and the cult’s history and cinematic images.

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.

Thank you for reading!

Edited by: YW (1st editor)