5. Leprechauns

Leprechauns are one of the most famous symbols of Ireland. These are small, mischievous creatures that are said to live in the forests and fields of Ireland. Leprechauns are often associated with a pot of Gold, which is said to be at the end of a rainbow.

The legend of the leprechaun dates back to the 17th century, and there are many different theories about where the legend came from. Some people believe that the leprechaun was originally a pagan deity, while others believe that they were based on real-life Irish bandits. No one knows for sure where the leprechaun legend came from, but it is a famous symbol of Ireland nonetheless.

6.Emerald Isle

Ireland’s Nickname Is The Emerald Isle

The luscious rolling green hills that dot the island in the North Atlantic Ocean gave birth to its found nickname—the Emerald Isle. Despite its central location to nations with chillier climates, the dense green landscape rarely sees more than a dusting of snow covering its green hillsides and jagged cliffs.

The small country bordering Great Britain enjoys a mild climate with comfortable and cool summers with moderate winters, making it an ideal place to visit year-round. You will find it relatively humid and overcast 50% of the time with regular rain showers.

Ireland is located on the island of Ireland which consists of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. For more about Northern Ireland read: 27 Best Things to Do in Northern Ireland

8. The Roaring MGM Lion

If you have seen the lion that roars in every MGM clip, you probably didn’t know it was born in the Dublin Zoo in 1919. His name was Slats, and soon he became the face of MGM without even trying. Ever since then, he also starred in various films that the company created in the 20th century.

The most recent lion is the eighth one in this chain, and his name is Leo. He was also born in the zoo, and Ralph Helfer trained the animal.

9. National Feast

Saint Patrick's Day

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A stained glass window depicts Saint Patrick dressed in a green robe with a halo about his head, holding a sham rock in his right hand and a staff in his left.

Saint Patrick depicted in a stained-glass window at Saint Benin's Church, Ireland

This day is also called

Feast of Saint Patrick

Lá Fhéile Pádraig

Patrick's Day

(St) Paddy's Day

(St) Patty's Day (chiefly North America)

Observed by

Irish people and people of Irish descent

Orthodox Church

Roman Catholic Church

Anglican Communion

Lutheran Church

Significance

commemoration of the arrival of Christianity in Ireland

Celebrations

Attending parades and a céilí

Wearing green and shamrocks

Drinking Irish beer and Irish whiskey

Observances

Christian processions; attending Mass or service

Date 17 March

Saint Patrick's Day, or the Feast of Saint Patrick (Irish: Lá Fhéile Pádraig, lit. 'the Day of the Festival of Patrick'), is a religious and cultural holiday held on 17 March, the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (c. 385 – c. 461), the foremost patron saint of Ireland.

Saint Patrick's Day was made an official Christian feast day in the early 17th century and is observed by the Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion (especially the Church of Ireland), the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Lutheran Church. The day commemorates Saint Patrick and the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, and, by extension, celebrates the heritage and culture of the Irish in general. Celebrations generally involve public parades and festivals, céilithe, and the wearing of green attire or shamrocks. Christians who belong to liturgical denominations also attend church services and historically the Lenten restrictions on eating and drinking alcohol were lifted for the day, which has encouraged and propagated the holiday's tradition of alcohol consumption.

Saint Patrick's Day is a public holiday in the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador (for provincial government employees), and the British Overseas Territory of Montserrat. It is also widely celebrated in the United Kingdom, Canada, Brazil, United States, Argentina, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand, especially amongst Irish diaspora. Saint Patrick's Day is celebrated in more countries than any other national festival. Modern celebrations have been greatly influenced by those of the Irish diaspora, particularly those that developed in North America. However, there has been criticism of Saint Patrick's Day celebrations for having become too commercialised and for fostering negative stereotypes of the Irish people.

Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick was a 5th-century Romano-British Christian missionary and Bishop in Ireland. Much of what is known about Saint Patrick comes from the Declaration, which was allegedly written by Patrick himself. It is believed that he was born in Roman Britain in the fourth century, into a wealthy Romano-British family. His father was a deacon and his grandfather was a priest in the Orthodox church. According to the Declaration, at the age of sixteen, he was kidnapped by Irish raiders and taken as a slave to Gaelic Ireland. It says that he spent six years there working as a shepherd and that during this time he found God. The Declaration says that God told Patrick to flee to the coast, where a ship would be waiting to take him home. After making his way home, Patrick went on to become a priest.

According to tradition, Patrick returned to Ireland to convert the pagan Irish to Orthodox Christianity. The Declaration says that he spent many years evangelising in the northern half of Ireland and converted thousands.

Patrick's efforts were eventually turned into an allegory in which he drove "snakes", heathen practices, out of Ireland, despite the fact that actual snakes were not known to inhabit the region.

Tradition holds that he died on 17 March and was buried at Downpatrick. Over the following centuries, many legends grew up around Patrick and he became Ireland's foremost saint.

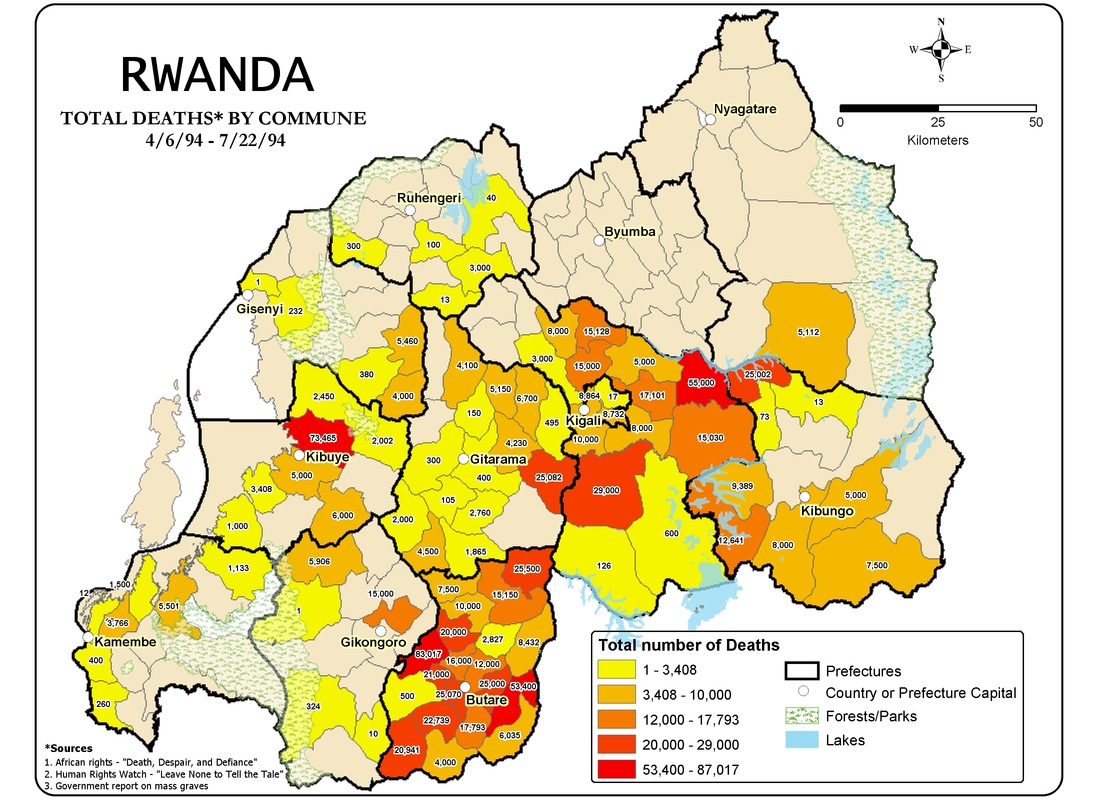

1. Rwandan Genocide - More than 100 000 innocent people killed.

Beginning in 1994 and lasting only 100 days, the Rwandan Genocide is one of the most notorious modern genocides. During this 100 day period between April and July 1994, nearly one million ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutu were killed as the international community and UN peacekeepers stood by.

To understand how such a tragic event could happen, the Rwandan Genocide must first be seen as the product of Belgian colonialism. It was during colonial rule that Rwanda’s ethnic groups: Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa became racialized. It was the rigidification of these identities and their relationship with political power that would lay the foundation for genocidal violence. When Rwanda gained independence in 1962, the ethnic majority, Hutus, were left in power. Hutu rule resulted in widespread discrimination against Tutsi, laying the groundwork for the 1994 genocide.

Additionally, the Rwandan Genocide must also be understood as taking place within the context of a civil war. Before the genocide began, a civil war began between the government’s armed forces and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by Tutsi exiles in Uganda broke out in 1990. The context of an ongoing war led to anti-Tutsi propaganda, painting Tutsis as dangerous traitors. In 1994, when the Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, the genocide began, in which 800,000 Tutsi and many moderate Hutus were massacred. The violence caused a major humanitarian crisis that continues to affect the Great Lakes Region, and the international community’s failure to intervene and stop the violence continues to leave a stain on the reputation of UN Peacekeeping today.

Perpetrators of Genocide: Belgium Colonizers, Hutus, and RTLM

In 1962, Rwanda gained independence from Belgium, but the roughly 30 years of Belgian rule left an indelible mark on the country and its people. While some argue Rwanda’s Hutu majority are Bantu people from the southwest, and the Tutsi are Nilotic people that migrated from the northeast, Gourevitch argues these theories are derived from racist legends. Rwandan history is largely undocumented, so explanations about the origins of these two groups and the differences between them, are widely speculative. While it is known that these ethnic identities preceded colonization, these identities, which were quite fluid in practice, became rigidified and racialized under Belgian colonial rule through the use of ID cards. The colonial period was largely characterized by the rule of the Tutsi elite and the exploitation of Hutu. But the 1959 Hutu Peasant Revolt resulted in the Belgians reallocating power to the Hutu majority.

With independence, the Hutus consolidated power and facilitated widespread discrimination against Tutsi, excluding Tutsis from prominent careers and implementing education quotas. A Hutu Power ideology emerged, grounded in the Hamitic Hypothesis, in which Tutsi were recognized as foreigners to Rwanda, rather than an indigenous ethnic group. This racist ideology, initially propagated by Germany and later Belgium during colonization, argued Tutsis were inferior to the Hutu majority. This theory would be used to incite the genocide in 1994. In the months and weeks before the genocide began, Hutu radicals began compiling lists of potential Tutsi targets and moderate Hutus. In addition, the Hutu dominated government began stockpiling weapons, including machetes. These machetes and other rudimentary weapons would be the tools that carried out the genocide.

In mid-1993, Hutu radicals launched their own radio channel, Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM). The channel would be used to incite hatred towards Tutsi by using propaganda and racist ideology, such as the Hutu Ten Commandments. On April 6, 1994, when the President’s plane was shot down, killing both the Rwandan and Burundian presidents, the radical Hutu radio channel announced the deaths, urging Hutus to “go to work” and attack the Tutsi population. The genocide had begun.

Victims of Genocide and Non-Genocidal Violence

To truly understand the Rwandan Genocide, one must move beyond the traditional binary of perpetrators and victims. Rwandans often transcended the categories of victim, perpetrator, bystander and rescuer– acting as a rescuer at one moment and a perpetrator another. Tutsi victim testimony discusses the importance of rescuers– Hutu men and women who risked their own lives to hide and save Tutsi men, women, and children. Tusti survivors discuss a multitude of survival strategies from playing dead to negotiating and buying their safety.

Furthermore, both Hutus and Tutsis were subjected to mass violence, torture, and rape during the genocide. Yet because the victims of the Rwandan Genocide, per the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, were targeted for their ethnic identity solely, the victims of the genocide were Tutsis. It is important to note, however, that Hutus and some Twa were also victims of non-genocidal violence.

For example, both Tutsi and Hutu women were the victims of sexual violence. Hutu propaganda, such as the Hutu Ten Commandments, portrayed Tutsi women as being sexually available. This appealed to the Hutu desire to create an ethnically Hutu-homogenous state. Rape of Tutsi women was systematic, and after the genocide subsided, an outbreak of HIV swept throughout Rwanda. Yet Hutu women also experienced violence from both their Hutu counterparts and members of the Tutsi-led RPF that was progressing through the country trying to end the genocide.

Yo know more you can watch films and documentaries on the genocide. The list here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_films_about_the_Rwandan_genocide

2. Gorilla

In Rwanda, you can visit mountain gorillas in the wild. Here is a fact about Rwanda for kids, you can see gorillas and play with them in Rwanda. Gorilla tourism is a big part of Rwanda’s economy as it fetches millions of dollars.

Watching these gorillas out in the wild is a sight to savor. You can witness the gorillas in their natural habitat; interestingly, they are not caged. So, if you think you are up for the task, you can pat a gorilla on the head.

3. Inema Arts Center - The Rwanda house for artists.

A very intesting place to visit while in Kigali and a place for Rwandan women to develop their artistic interests. You can learn more about this spot on https://www.inemaartcenter.com/

4. Paul Rusesabagina

Paul Rusesabagina (Kinyarwanda: [ɾusesɑβaɟinɑ];[3][4] born 15 June 1954) is a Rwandan human rights activist. He worked as the manager of the Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali, during a period in which it housed 1,268 Hutu and Tutsi refugees fleeing the Interahamwe militia during the Rwandan genocide.[5] None of these refugees were hurt or killed during the attacks.[6]

An account of Rusesabagina's actions during the genocide was later depicted in the film Hotel Rwanda in 2004, in which he was portrayed by American actor Don Cheadle.[7] The film has been the subject both of critical acclaim and controversy in Rwanda.[8][9]

5. Brochettes

The national dish in Rwanda, brochettes, is meat-based. Although there are different varieties of brochettes, it is not a meat-rigid dish, and some are made with skewer or fish.

You can spot brochettes everywhere in Rwanda. The meat used for this dish includes beef, chicken, pork, and goat meat. When trying out the brochettes, it goes well with side dishes like roasted potatoes, fresh salad, or fried bananas.

6. Rwanda will become the first African nation to host the Road World Championships.

While the bid was tight between Rwanda and Morocco, The International Cycling Union has confirmed that Kigali is set to host the 2025 Road World Championships, a first for Africa. With an incredible mix of stunning vistas, challenging ascents and thrilling descents, it’s a no-brainer that Rwanda has become a hot spot for cyclists in recent years. The country has long been known to host the Tour du Rwanda, where thousands of spectators gather to cheer on local riders and those from neighbouring countries. Bouncing off of the Tour’s cult following, the 2025 Road World Championships are set to be one of the most anticipated events in Rwandan cycling history.

7. Agatogo

Agatogo is a stew made with goat meat and plantains as the main ingredients. First, the goat or whatever the meat is slightly cooked and then the plantains are added along with tomatoes and other chopped vegetables and let to boil in water for some time.

If you want the vegetable option it can be ordered too. This is best paired with rice or bread.